Who Cares If It's True?

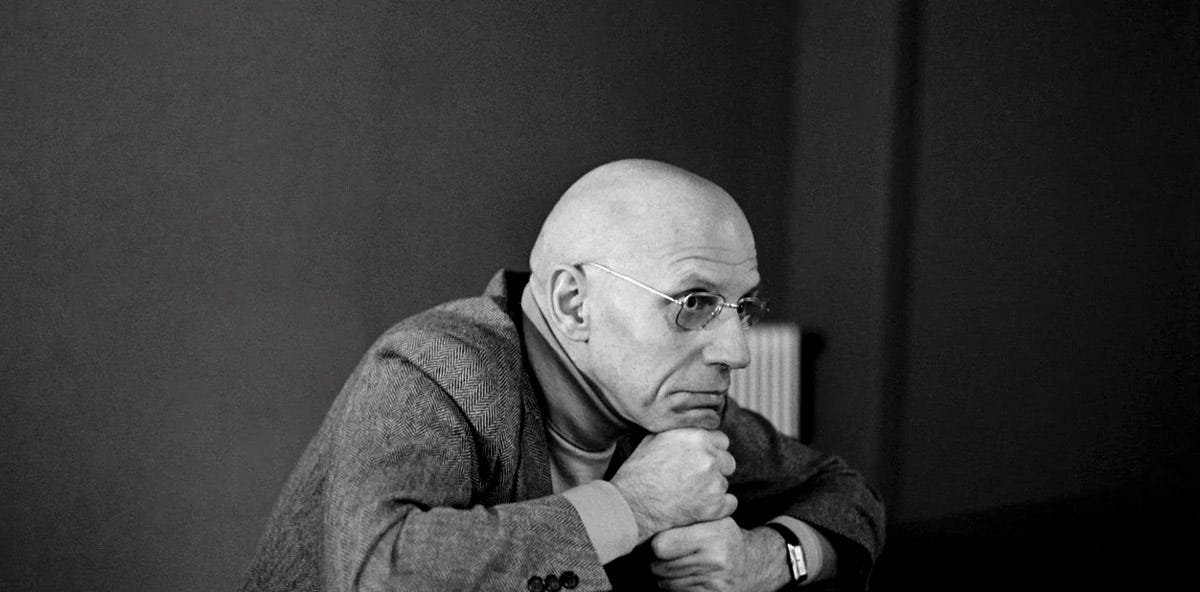

The other day during a seminar, one of my lecturers made a dashed-off comment about philosopher and historian Michel Foucault. "Most of what he wrote isn't true," the lecturer said, waving a papery hand dismissively, barely drawing a breath before barrelling onwards to the next point. He never returned to Foucault again.

The comment stuck with me. Mostly because I was annoyed -- I have long loved Foucault. He was an early philosophical influence, and I fell in love with his dense, alien prose when I was only a teenager. Even now, many re-readings in, I marvel at the way he can snap between historical narratives and deep, Freudian analysis in an instant, and his work has always felt underwritten by a sense of unpredictability to me, the thrill of wondering what he'll get up to next.

Which is the thing: unlike so many of the other canonical voices in the discipline, Foucault was fun, not only as a writer, but as a man. He liked drugs — acid, he said, had transformed his thinking permanently — dressed well, gave barbed interviews. One time, he got hit by a car, and later said that the incident remained one of his fondest memories. Even at his most serious, he always appearsto be winking at you. There aren't many big names you can say that about.

And yet, the more I mulled on the lecturer's comment, the more I realised there was something else keeping it stuck in my craw. I wasn't just insulted by what he had said. I was oddly surprised by it. I suppose, all things considered, I had never really thought Foucault's best quality was his accuracy. Should I have been worried about such matters? Was I an idiot for not considering them?

Over the next few days, I researched Foucault's falsehoods. There were more than I was expecting. He misused data, most agree; twisted stories to fit a thesis; even misrepresented the work of some of his contemporaries. The History of Sexuality, his multi-volume exploration of changing social mores, has been accused of warping more truths than it uncovers.

But when I re-read the first volume of that series, The Will To Knowledge, with such flaws in mind, I realised that it was true: I actually didn't care how much of Foucault’s writing reflected the real world. In fact, his misrepresentations seemed rather thrilling to me. The book now read like a man wrapping the facts of the world around his little finger, a bending of reality. I had always read Foucault for the fireworks. They still remained. Who cared if "truth" was up in the air?

Moreover, Foucault seemed to enjoy reading such ludicrousness himself, without ever worrying about its potential truth values. In his introduction to Anti-Oedipus by Gilles Deleuze and Feliz Guatarri, a work of political writing that tries to prove capitalism has fractured and atomised us while opening with a long section about “anal machines”, Foucault encourages the reader to leave reality out of the picture. “One must not look for a ‘philosophy’ amid the extraordinary profusion of new notions and surprise concepts in this book,” he writes. “I think that Anti-Oedipus can best be read as ‘art.’”

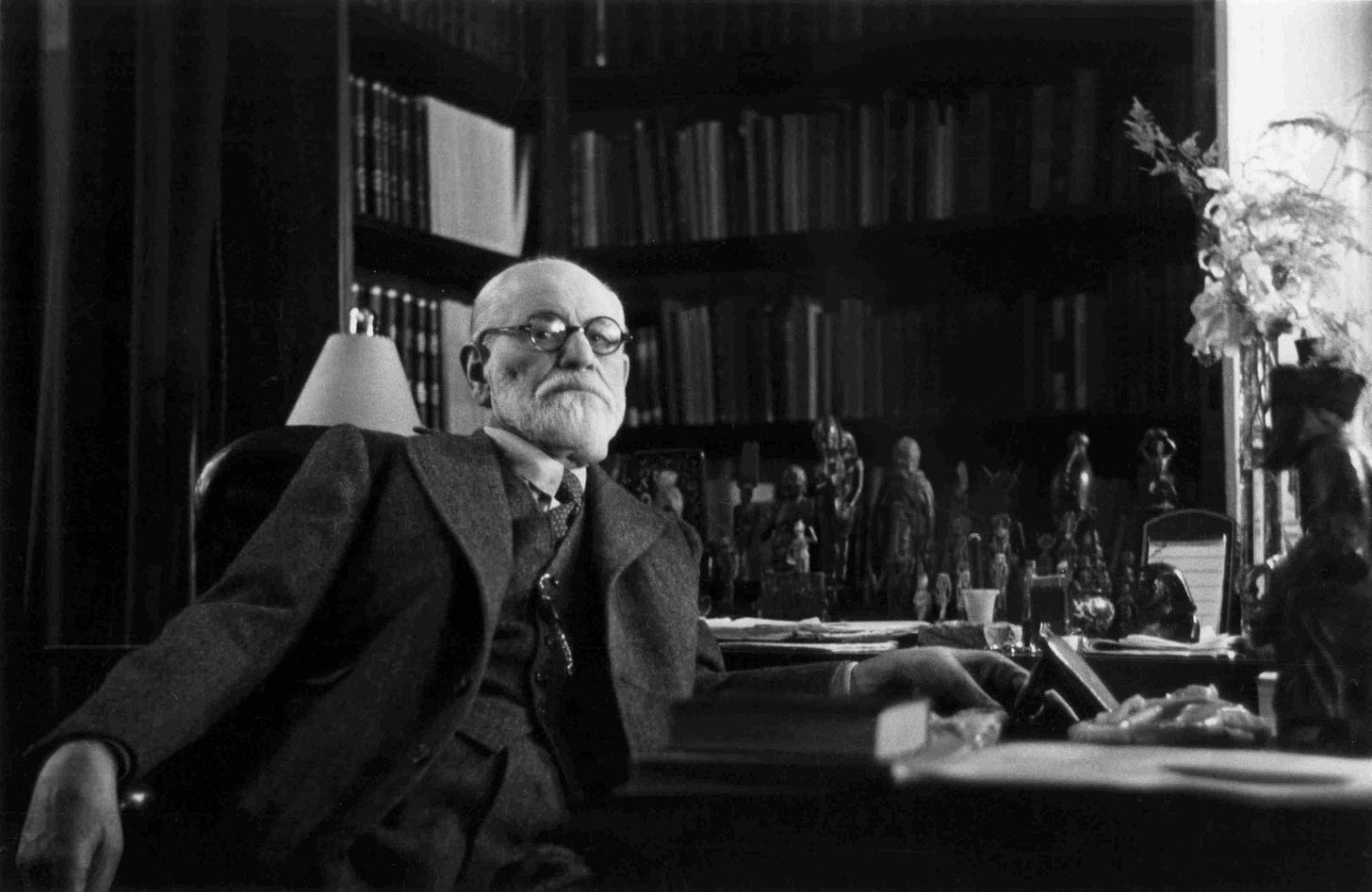

Honestly, I’ve always found Freud fun to read in the same way. His short paper "Dostoevsky and Parricide", which I re-submerged myself in with the help of a reading group earlier this year, is the high bar for such entertainment. A supposed untangling of the Russian author's epilepsy, Freud claims Dostoevsky's medical woes were born by a desire to kill and replace his father. That's not only pseudoscience, it's also factually wrong -- Dostoevsky's seizures started long before Freud claims they do in the paper. And yet the whole piece is joyous precisely because it's so wrong; because the claims it makes on reality are greater and more outsized than any imaginative leaps in fiction.

Deep in the essay, after explaining a series of castration fantasies he has implanted in the head of Dostoevsky, Freud apologises. "I am sorry, though I cannot alter the facts, if this exposition of the attitudes of hatred and love towards the father and their transformations under the influence of the threat of castration seems to readers unfamiliar with psycho-analysis unsavory and incredible," he writes. It's a beautiful moment -- an explanation for psychobabble that attempts to make the reader feel unhinged, rather than the wizened magician assembling the words. I believe there are few more amusing, warm, or oddly touching sentences in modern literature. Because sitting in the middle of those few short lines is a whole human being, Sigmund Freud, and he's explaining how the world appears to him, without shame.

Maybe it sounds like I'm suggesting Freud and Foucault can be read as fiction. But that's not quite right. If "Dostoevsky and Parricide" was written as a short story, it'd be dry; aimless. The sparks come from its supposed relationship with the truth -- this is what someone really thought, and felt confident enough to put down on a page and assert as truth. It might not be "real" in the way we tend to consider that word; as in, backed by science. But it's someone's reality. And that's the joy.

Of course, there must be a limit to this fun. Lies dressed up as truth are scrambling our political systems and our current response to the global health crisis. Conspiracy theories, a warped reading of reality on par with some of Freud, aren't just absurd word-games. They're an actual harm. We should be diligent about separating the claims made by our best science, and the ones that are not. But once we have done that separating -- once we have snipped a paper like "Dostoyevsky and Parricide" of its wannabe status as a work of truth-telling -- I think we can submerge ourselves in the joyous slop of it all; in the ever so slightly different, clustered takes on reality that surround us in the minds of our friends, enemies, and colleagues every day.

Richard Rorty, the American pragmatist philosopher, thought that it was useless to develop a system of "truth". He didn't believe that we could ever stand in direct relation to a non-human group of facts -- there is no way we can ever know things ahistorically, on his account. We're all too tied up in contingency, and our brains aren't the perfectly polished mirrors of nature we sometimes consider them. Therefore, Rorty gave up on some absolute "reality", and settled instead for a contingent, deeply historical "correctness", one he knew could change over the years, and expand and grow.

That, I think, is part of the joy of reading these fictions-as-truths. We're charting the changing coastlines of our historical, contingent understanding of reality. And reminding ourselves that even the things we most take for granted as real might alter and change, slipping away from under our feet, without us really noticing.