All My Spaceships

A few pages into ‘Pilgrimage’, Susan Sontag’s account of the time she and an adolescent friend crashed Thomas Mann’s Southern Californian house, she carves out a few lines about her book collection.

She writes:

“I never thought of going to a library. I had to acquire my books, see them in rows along a wall of my tiny bedroom. My household deities. My spaceships.”

I read the lines in the bath, at the end of a long, somewhat stressful week. They moved me. I have the same connection to my books; the same sense of awe. I too need to own, not to borrow. And when I’m feeling down, I also look at my books in their messy rows, stacked in shelves that flank the dining room table, and feel settled.

Susan Sontag

This edition of the newsletter is something like that process of looking. It’s a list of the six books that have had the greatest impact on me, arranged in the chronological order of the time that I met each of them.

There are other caveats. In order to avoid becoming a broken record already, I have avoided the big names I invoke in this newsletter time and time again — there are no books by Sontag, Mark Fisher, or David Hume in this list. I’ve also only chosen one book per author, and tried to cover as much of my reading habits as possible.

Lists like this are of course kind of arbitrary in a lot of ways; boiling down a couple of decades of reading into this strange, lopsided little bit of autobiography. But that’s what makes them fun, I reckon.

1. John Berger — Ways of Seeing

My last few years of high school hurt me. I wasn’t sleeping well. I had only a few friends — sometimes, not wanting to face anyone, I ate my lunch sitting in a locked toilet cubicle, crumbs spilling into my lap. Just before graduation, I started having near-constant nosebleeds. The worst was when they’d hit me while I was on the bus home. I’d sit up the front, my nose plugged up with grotty bits of tissue, and think about crawling into the biggest, dampest hole I could find.

The classes themselves were mostly uninspiring. Art History was particularly painful. The teacher, a short man with slicked back hair and glasses as thick as Coke bottle bottoms, read from sheaths of notes that he had prepared years earlier, barely looking up from the page while he droned at us.

Then, a few weeks into term, he pulled down the blinds, unfurled a projector screen, and told us we were going to spend the next few weeks watching a television series about art. It was good, he told us — very famous, though the host was a little “daggy”. Then he pressed play on the first episode of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, walked to the back of the classroom, and almost immediately fell asleep.

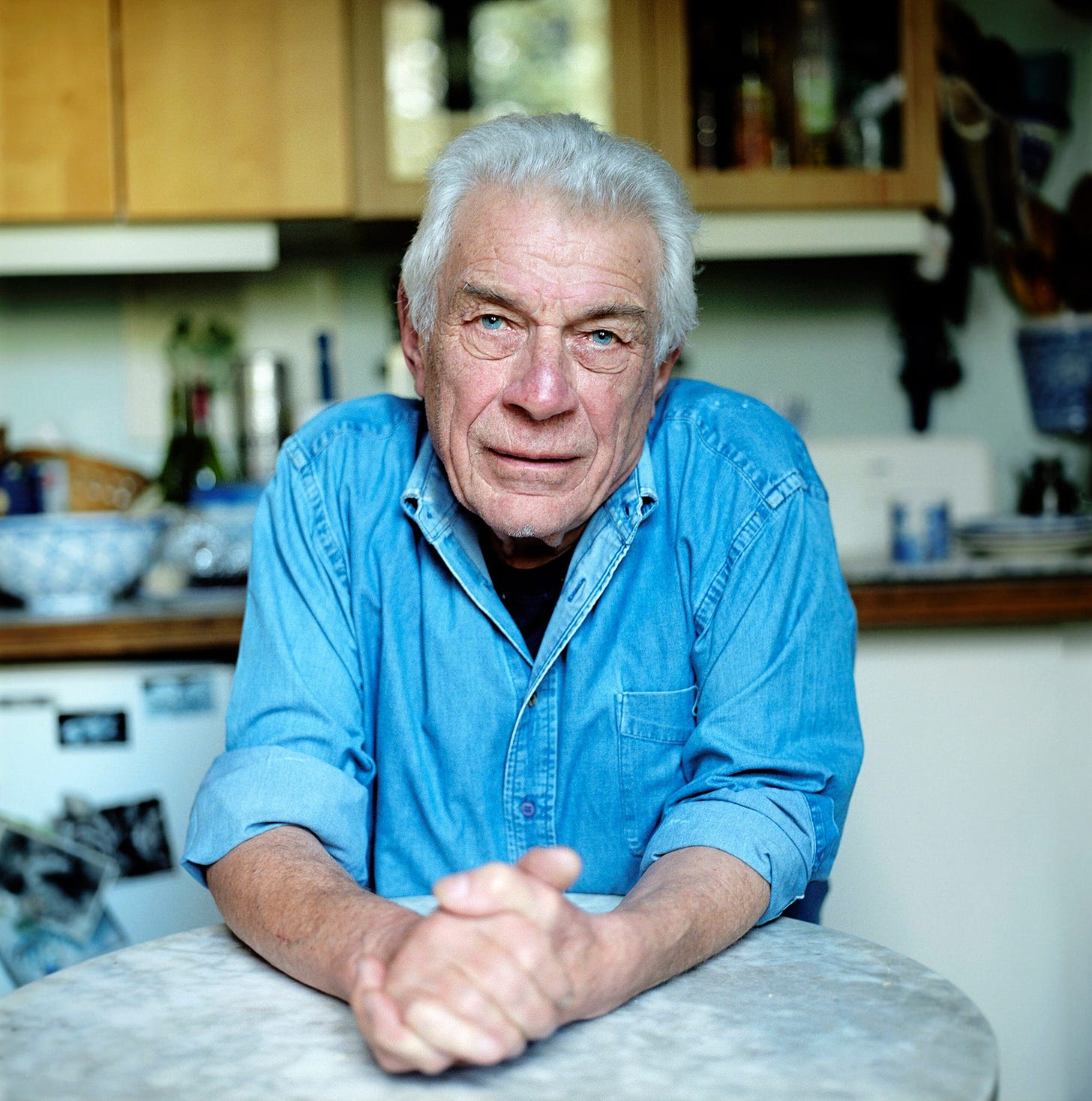

John Berger

In the very first scene of Ways of Seeing, Berger walks up to a priceless canvas, removes a knife from his pocket, and cuts out a square of the image. Later, his boofy hair tucked behind his ears, looking something like a Cocker Spaniel, he sits around a group of children, and asks them to poke apart a reproduction of Caravaggio.

At the end of the 40 minutes, Berger goes meta. “Remember,” he says, looking straight into the camera, speaking in his solemn lisp, “I am controlling and using for my own purposes the means of reproduction needed for my program.”

I had never seen anything like it before. My brain was lit on fire. I grew tetchy and crooked, desperate to see the next episode. But I couldn’t wait. A few days later, on my way home, I bought the slim, boxy paperback copy of Ways of Seeing, the text version of many of the speeches Berger gives over the course of the series, and read it time and time again.

Early on, Berger reproduces a painting of a corn field, and tells you it’s a Van Gogh. When you flip over the page, he shows you the same image again, but this time gives you the context — it was the last painting Van Gogh produced before he killed himself.

The book is full of such tricks. But they are not tricks at your expense. They are designed always to reacquaint you with images; to get you to notice all of the subliminal forces you have come to take totally for granted. Most of the time, such forces are political. Ways of Seeing is suffsed with Marxist ideology, and Berger writes with more intelligence and insight than almost any of his contemporaries on the subject of marketing and advertising.

Ways of Seeing was an entrance to about a dozen different intellectual worlds — political, aesthetic, historical. It became something like a Bible. Indeed, it had such an early and immediate impact on me that I convinced myself I wanted to be an art historian. It was only after years of trudging through uninspiring essays with none of the spark I had found in Ways of Seeing that I realised I hadn’t fallen in love with writing about art. I had fallen in love with John Berger.

2. Flannery O’Connor — A Good Man Is Hard To Find

I also read Flannery O’Connor for the first time during my last few years of high school, her story ‘Good Country People’ dished out as part of a compendium of short fiction we read while preparing for the HSC. But while Berger had inspired me, O’Connor freaked me out.

‘Good Country People’, a story of hucksters and bumpkins, seemed curiously amoral in a way I couldn’t handle. It was full of bad people doing horrible things to one another, which I already loved from art — I was a full-blown slasher film addict by this stage. But O’Connor seemed to be standing a couple of steps back from the page in a way that disquieted me. I couldn’t tell what she thought about anything that her characters were doing, or if she even liked them.

That feeling only intensified when, a few years later, I stumbled across a battered copy of A Good Man Is Hard To Find. The titular story, perhaps O’Connor’s most famous, was similarly unsettling — like a fable with all the meaning snipped out. Following a family who have a violent encounter with a murderer, the story eventually breaks down into what is either a kind of redemption, or an awful, pointless death. I couldn’t make sense of any of it.

I knew, thanks to the internet, that O’Connor was a Christian; that some had read her stories as parables about the light of the Savior. But they were so weird; so unpleasant. They were like no religious texts I had ever encountered. I read the whole collection, but slowly, taking long breaks, and wiping my hands after I had turned every page, as though the book was slick with something I didn’t want to stay on me.

Flannery O’Connor

It did stay on me, of course. Eventually, I stopped trying to crack O’Connor, and just let her happen, whizzing through the wet joy of Wise Blood, and eventually turning to her letters. The autobiographical stuff only confused me more — in correspondence, O’Connor was a bashful young woman who liked peacocks more than people, and who had a gee whizz energy at total odds with the darkness latent in her pages.

As she often liked to remind people, a camera team had once filmed a chicken she taught to walk backwards when she was only a child. In all of her personal writings, she shares the exuberance and wide-eyed wonder that she had once exhibited as young “Mary” O’Connor, showing off a bird to some cameras.

I still don’t really understand O’Connor. Those who want to read her as a Christian moralist get her wrong, I think. The joy is in not seeing her trace a world that we kind of know. It is watching as she delicately, insistently scrambles the one in which we live.

3. Kay Redfield Jamison — An Unquiet Mind

I had always hoped that my life might immediately and irreversibly improve when I left high school. It didn’t, of course. The nosebleeds went away, but the insomnia and anxiety mostly didn’t. Only occasionally, once every month or so, did I feel freed from nervous thoughts. And then, the freedom was strange; rather alien.

The problem was, when I felt good, I felt really good. I bounced off the walls. One night, when I was no older than 20, I watched a documentary about the singer Leonard Cohen and decided that there was no-one brighter, better, or smarter who had ever lived. I was so excited I took a long walk. It was perhaps two in the morning, and there I was, marching up and down darkened streets, talking to myself, filled up with the light of a Canadian singer-songwriter.

Moreover, these episodes were growing more intense. Once, I sat in a rainy park, listening to the same section of ‘Blister in the Sun’ by the Violent Femmes over and over, until someone approached and tried to mug me. A few months later, I decided I needed to walk more, and so began to hike around my local beaches for six hours at a time, until my feet were swollen with blisters and I got mild heatstroke. During one particularly intense episode, I decided that houses were unnecessarily, and spent a few days living on the street, until I got so sick I had to spend a week in bed.

In writing about those days now, it still seems incredible to me that none of the many doctors or therapists I saw delivered the obvious diagnosis — that I had bipolar, a manic-depressive pattern I tried to self-medicate with alcohol. But it took them a long time to get there. Even after a stay in a psych ward, the best they could manage was an OCD diagnosis. When I didn’t improve, a new therapist suggest it might be depression. They put me on a range of medications. And still, I drank.

It was around this time that I found a battered copy of Kay Redfield Jamison’s An Unquiet Mind in my local bookstore. I’d like to say I was drawn to it. But actually, I don’t remember why I bought that book, with its unassuming blue cover, and a generic Oliver Sacks quote on the back. Hard not to use “fate” when talking about such encounters, to be honest.

It was in the pages of An Unquiet Mind that I first really saw myself. Jamison, a clinical psychologist who discovered that she had bipolar disorder while studying as a young woman, weaves the lived experience of the disorder with its more clinical outlines. Back and forth she hops between her own version of Leonard Cohen nights — moments she found herself filled with an indescribable energy; a light — and the history of the illness; how it has been treated and seen.

A few weeks after I read the book, I went and saw my therapist. “I think I have bipolar,” I told her. A few weeks later, I had the diagnosis, a treatment plan, and a prescription for mood stabilisers. There are a lot of books on this list that mean a lot to me. But An Unquiet Mind is the book that saved my life.

4.Thomas Ligotti — Songs of A Dead Dreamer / The Conspiracy Against The Human Race

I was 13 when I read an interview with my idol, Stephen King, in which he said he owed everything to some old timey dime store pulpsmith named HP Lovecraft; 14 when I powered through every stained Lovecraft paperback I could find; and 16 when I started reading terrible entries into the Cthulhu canon that people who mostly wrote Warhammer fan fiction composed on archaic blogs in their spare time.

I was obsessed with the Lovecraftian world, packed with its Old Gods and ancient evils, and bristling with the promise that human beings were much less important than we all considered ourselves to be. But I had burnt through the good stuff too fast. Other than re-reading stories like ‘The Rats in the Walls’, all I could do was terrify my ex-partner by suggesting I might get a Cthulhu tattoo, and hope to eventually find someone in the same league as Lovecraft.

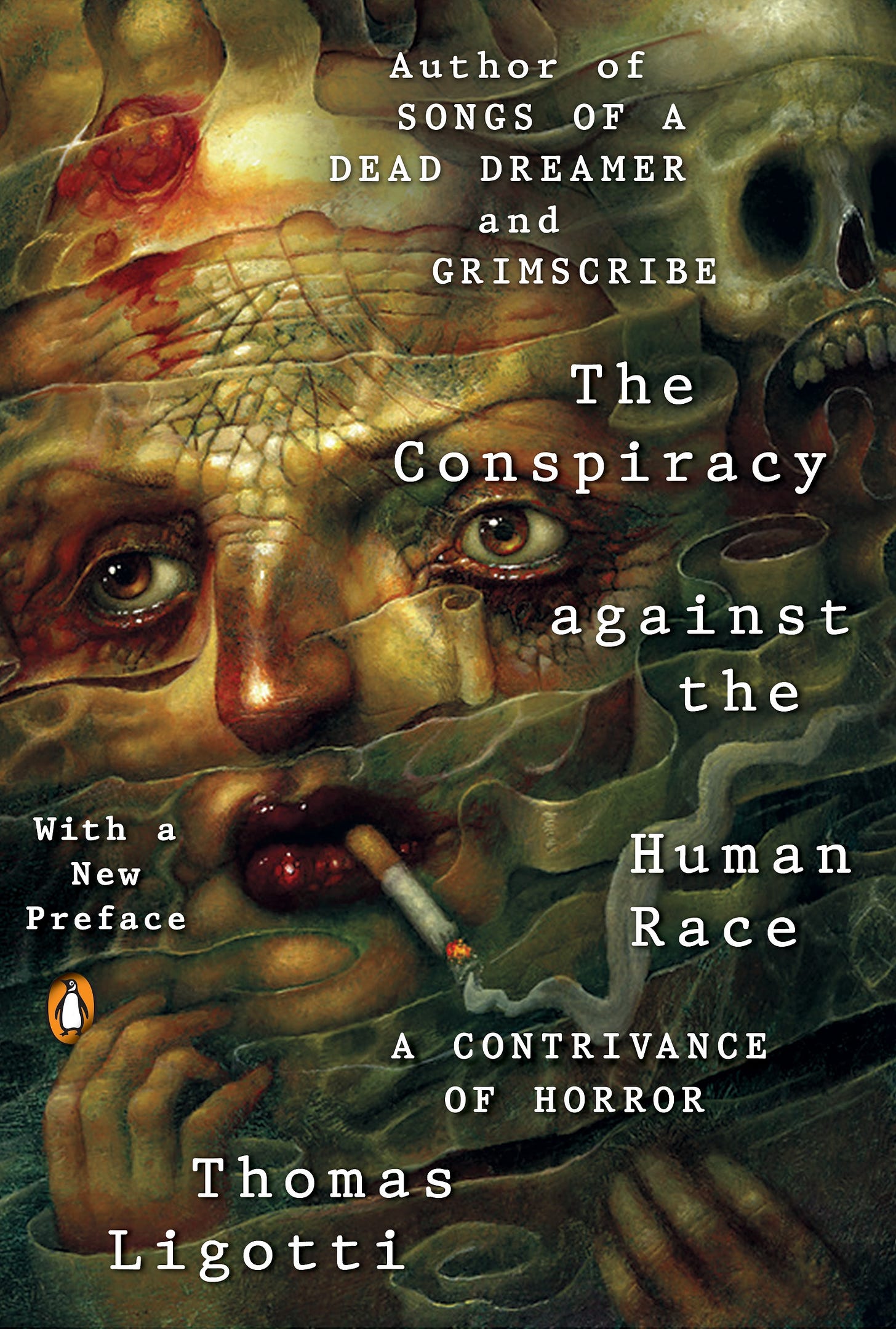

It was many years later that I stumbled across Thomas Ligotti, a writer of eerie horror and speculative fiction. When I first started reading him, his books were impossibly hard to find, selling for outlandish prices on ebay. So I read Grimscribe, his second collection of short fiction, on a blurred photocopy on a glaring PC screen, scrolling through a PDF someone uploaded to one of the horror forums I visited.

In a way, that only added to the experience. It really felt like I was reading something illicit; dangerous. Some of the stories, like ‘The Mystics of Muelenburg’, genuinely upset me. I’d lay there in bed, staring up through the ceiling, and fret about what I had read.

Eventually, Ligotti’s back catalogue was published in full by Penguin. For the first time, I read Songs of a Dead Dreamer, his debut fiction collection, and The Conspiracy Against The Human Race, a work of philosophy in which Ligotti argues that to live is to suffer, and that self-extinction is the only admirable option for the human race.

This position is called anti-natalism, and Ligotti is its most fervent, if poetic, subscriber. Towards the middle of The Conspiracy, he writes:

“To keep our minds unreflective of a world of horrors, we distract them with a world of trifling or momentous trash. To stabilize our lives in the temepstuous waters of chaos, we conspire to anchor them in metaphysical truths — God, Morality, Natural Law, Family — that inevriate us with a sense of being official, authentic, and safe in our beds.”

For Ligotti, all pleasures are a lie. The only truth is suffering, and the only escape is death.

I like books, my dog, my partner, and the steel sculpture of a cockatoo that sits above my desk too much to subscribe to this belief. But I am electrified by it. That a human being, Ligotti, sat down at a desk every day for many months and wrote a long treatise about how awful it is to be alive is both somewhat amusing and genuinely touching to me. His work is a reminder that you can never be too outrageous; that the joy of reading another is having a separate reality come crashing messily into yours like a black comet, flung into your orbit by an ancient octopus God.

5. Maggie Nelson — The Argonauts

I was in my mid-20s when I discovered Nelson. My friend Adele, who I used to trade books with, threw me a copy of The Argonauts one day, a bus ticket tucked just inside. “You’ll like this,” Adele said.

I did. Nelson’s book, which is divided up into short, concrete ideas — a la Wittgenstein’s Tractatus — blends philosophy with autobiography; the particular with the universal. There are tangents on the work of John Waters, on maternity, on Emerson. Throughout much of the book, Nelson wrestles with her own sexuality; she is a woman dating a trans man, so she feels as though she can appear a hundred different ways in a hundred different contexts — straight at a parent-teacher interview, queer at an art gallery opening, and so on, ad infinitum.

I still thought of myself as straight when I read The Argonauts, despite the fact that I had many romantic and sexual relationships with men in the past; some serious, some short. I don’t know why I used that label. I guess I just didn’t think about it much. I was an undiagnosed alcoholic then, so there were a lot of things that I didn’t think about. Drinking takes up so much mental energy, you don’t often have the strength to work on re-categorising yourself or questioning the easy assumptions that underpin your personality.

Maggie Nelson

But Nelson made me do the work. As she settled her own complex feelings about her sexuality — were there people who just considered her “queer by default?” Did she really count as part of the community? — I started to as well. It would take getting sober before I properly understood myself as bisexual. But the book shifted something. I remember handing it to Brianna, my partner, just after I had finished it, trying to play off the impact it had already had on me.

“You’ll like this,” I said to Brianna.

And then a few years later, when I had finally gotten sober, and I felt like I could be honest to Brianna about my relationships with men, I invoked The Argonauts in explaining myself. “That book helped me,” I told Brianna. And it really did.

6. Derek Parfit — On What Matters

Around the time Adele introduced me to Nelson, I quit a job in special needs education I’d held for seven long years. I finally felt in a place where I could give being a writer a proper go, and was already picking up a little work in music criticism. It was a now or never moment, I suppose, and I was ready to suffer a little in order to live my dreams.

Brianna and I lived with three of her friends in a tiny house with a broken toilet. We fretted about money constantly. Often, Brianna had to cover my part of the rent. The editor who I worked with most closely seemed to like me, but did little to throw me more opportunities. He’d make me beg him for interviews like the rest of the freelancers, keeping my phone on me at all times so I could respond to his call-outs as soon as they hit the mailing list. Then, with as much paid work as I could get nailed down and fuelled by giant mugs of instant coffee, I’d write 900 word profiles for him of Melbourne bands no-one had ever heard of. I’d get paid $30 a pop. Sometimes, if there were edits — and there usually were, because this editor was pedantic and driven — each article took a few days to get right.

And then, one Christmas, I decided I’d finally had enough. The magazine shut down over the holidays, and I was too poor to afford rent again. For a few months, I worked weekends with a young man with disability, providing in-home care. But he’d started violently attacking me. One night, after getting wrestled to the floor by him and slapped around the face, I told Brianna I didn’t think I could live like this anymore.

“What are you going to do?” they said.

I thought about it.

“I think I’m going to go to uni,” I replied.

My plan was to study history, for no real reason other than to collect the Austudy stipend and maybe end up being a high school teacher. I was frustrated, then, when the university told me that an undergraduate degree required doing other sorts of study, not just history. Barely paying attention, I selected a number of other units at random, and complained about the whole process a lot to Brianna.

One of the courses was an introduction to philosophy. The first lecture was a disaster — an hour-long rant about how to use the library. I almost un-enrolled. But the second lecture, led by a short man with wispy hair and a booming, theatrical voice, changed the direction of my life.

I can’t really remember what it was about now. Some kind of metaphysics; maybe theories of time? I just remember being electrified, filled up with new possibilities for thought. It was the experience of watching Berger on a beat-up projector screen again; of being reintroduced to all these background ideas I had taken for granted, and had thus made invisible.

In the months afterwards, I read voraciously, any philosophy I could get my hands on, encountering many of the names that are now deeply embedded in my academic practice — Kant, Hume, Korsgaard, Plato. But as a piece of writing, nothing made it so obvious that philosophy would take up the rest of my life as Derek Parfit’s On What Matters.

Derek Parfit

Parfit’s explicit project in the book is to prove the existence of moral laws. He doesn’t want to say that morality is conditional or subjective; something that we’ve just made up. He wants to take it for real — to say that even in a world without humans, “murder is wrong” would hold.

As part of that project, Parfit seeks to show that two of the biggest seemingly competing moral schools — consequentialism and deontology — are actually saying different versions of the same thing. After all, pulling off such a feat would be a way of showing how apparent moral facts are. We all know that they exist, Parfit wants to say. We just call them different things.

His project is therefore shockingly ambitious on at least two levels. Proving that “murder is wrong” is true in the same way that 2 + 2 = 4 is true takes a kind of gumption not found in most. Showing such a proof while also demonstrating that hundreds of years of philosophical arguments are actually over a mere difference of terms is even wilder. But it was the scale of the project that enticed me so. Over two thick, hardback volumes, Parfit brushed up against the impossible.

And hell, on first read, he seemed to be getting somewhere. Page after page, I was witnessing a man try to explain the world as he saw it, and having some success.

These days, I am less amenable to Parfit’s whole project. But I still love that book. Each time I pick it up it strikes me as more unhinged; more beautiful; more full of grace. It is thousands of words written by a Don Quixote running at ontological windmills, and I love it for its failures as well as its successes. It rings in my ears every day.